Yes, 10 seconds.

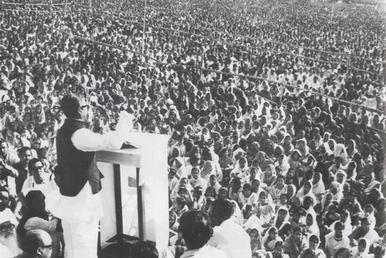

While celebrating anything about Sheikh Mujibur Rahman—there are scores of them– his party and sycophants have only one thing to show: a ten-second video footage of his March 7, 1971 speech, eliminating the remaining 1010 seconds of the delivery. As if that heavily edited ten-second oratory was the only thing their leader had to offer in his whole life. Let us recall those ten seconds and see what they contained and why Mujib did not live up to his words.

On March 7, 1971, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman declared: Ebarer songram swadhinotar songram…Ebarer songram amader muktir songram. (This time, our struggle is for independence, for freedom). But when the time for songram came, Mujib refused to join it. By March 25, 1971, the Pakistan military was poised with guns, tanks and planes to start the Operation Searchlight aimed at “teaching the Bengalis a lesson.” Alarmed, political and student leaders kept coming to Sheikh Mujib at his Dhanmondi residence that evening. All had only one request: “Please declare the independence of Bangladesh and get out of here. Lead the liberation war.” His deputy, Awami League Secretary General Tajuddin Ahmed, even brought a tape recorder for the announcement.

Mujib would do none of that. However, he had his own secret plan not known to anyone other than his family members. He had arranged through the US Ambassador in Islamabad his surrender and its terms (See Witness to Surrender by Siddiq Salik). It was to be a temporary arrangement until the agitating Bengalis were tamed, and Mujib then installed in the seat of authority in Islamabad. He sent his family members away but Begum Mujib stayed with him. As such, Mujib had reasons to refuse their requests. “If I declare the independence,” he made an excuse to Tajuddin, “Pakistan will try me for treason.”

The question is, why did the term “treason” come to Mujib’s mind at that crucial juncture of history? One doesn’t have to go far for the answer. He had a surrender plan locked in, and he would not make any moves to jeopardize that scheme or risk his life. To silence the visitors, he bluffed, “Go home and sleep tight. I called for Hartal (strikes) on March 27. (See Tajuddin: Pita O Neta by Sharmin Ahmed and accounts of Mohitul Islam). On March 7, Sheikh Mujib asked the people: Tomra ghore ghore durgo gore tolo (Make fortresses of your houses). He too made a fortress of his house: It was a fortress manned by the Pakistan military, not to fight the enemy, but to save itself from the Bangladesh freedom fighters.

Rokto jokhon diyechi, proyojone aro rokto dibo. Edesher manushke mukto kore charbo, inshallah (We shed blood in the past, we will shed more if needed; yet, I will make the people of this country free, God willing), he also said. But at the time of need, he quietly left the battleground for safety. None of his family members ever shed blood before the independence or during the war. His family was protected by the Pakistan military, which had been making Bangladesh its “killing fields” outside. What an oratorial bluff, which, however, had been a hallmark of Mujib’s politics!

Let us revisit the time and space to remind ourselves, as well as for the benefit of younger generations, which seem to have been brainwashed or confused with distorted history. After Sheikh Mujib proposed his 6 Points in 1966, the deprived people of East Pakistan were made to believe that it was the formula to redeem their rights from the West Pakistani overlords, even though they knew very little of what was contained in it. The 6 Points were essentially an economic idea in which provinces (mainly East Pakistan) would control all aspects of finance and trade. Nothing was in it about the foreign policy, military and national security. Taking advantage of the fact that past Pakistani leaders and their Bengali sycophants cheated them for years, Mujib successfully mobilized the East Pakistanis to accept him as their sole messiah.

A few Bengali civil servants claimed authorship of the 6 Points; Ruhul Quddus and AMA Muhit, were among them. Yet, another suggestion came from the most unlikely source: President Ayub Khan. To portray Sheikh Mujib a regionalist, he asked his powerful Information Secretary Altaf Gauhar to draft the points and discreetly pass it on to Mujib. Reportedly, Industrialist Abdullah Haroon of Karachi, a friend of Mujib, was the conduit. If so, it did not work for Ayub. In the face of growing unpopularity of President Ayub Khan in the late sixties, the 6-Point Formula gained momentum in East Pakistan and Mujib became the supreme leader there.

A frustrated Ayub played another dirty game. He implicated Mujib in the flimsy Agartala Conspiracy Case (ACC). The people of East Pakistan, led by elderly leader Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhasani and the All-Party Students Action Committee, filled the streets and fields with mammoth gatherings protesting the ACC. Noting the popular pulse, most other political leaders, including Pakistani minded Nurul Amin and Khan Sabur Khan, joined the call for Mujib’s release. Ayub not only lost the game, he catapulted Mujib to the height of popularity. Mujib became a fairy tale hero! People believed everything he said and they overwhelmingly voted him to be the majority leader in the elections of 1970.

Bhasani boycotted the elections as he had already declared that he had nothing more to do with West Pakistan nor its military leadership. It was open season for Mujib’s Awami League. General Yahya Khan, the new military leader since March 1969, started off well but soon faltered under the pressure of hawkish generals and Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, leader of the Pakistan Peoples Party, which gained majority in West Pakistan. President Yahya failed to bring Mujib to make compromises on his 6 Points so that the interests of the center and West Pakistani provinces could be accommodated.

Finally, he decided to play the ruthless general rather than a political leader: Mujib would not sit in Islamabad. In this backdrop, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman made his historic call on March 7, 1971: Ebarer songram… Yet, Yahya kept the Bengali leader in good humor in the name of talks from March 15 to 25, 1971 while militarizing the province to the teeth. What was surprising that Mujib consciously walked into the trap of the military junta and looked forward to be the next Pakistani leader, despite his March 7 call for Ebarer songram… Even as the military was standing ready for the genocide within hours, he checked with Dr. Kamal Hossain, the conduit, in the evening of March 25 if the president made the promised declaration making him the Prime Minister of Pakistan (Ref: Syed Badrul Ahsan of the Daily Star).

Could there be a worse political miscalculation in history? Shortly after midnight, Mujib and his wife were picked up by a Pakistani commando unit and taken to the newly built MNA Hostel at Sher-e-Bangla Nagar. After two nights, Mujib was taken to the Dhaka Cantonment and his wife was returned to his family, which was housed at 19 Dhanmondi, under military care. Apart from a fat cash allowance to the family, food provisions came from the cantonment. Sheikh Hasina delivered her son Joy at the Dhaka Cantonment in July amidst much fanfare and sweet distribution by the soldiers. Mujib’s father was Heli-lifted from Tungipara to Dhaka for a minor treatment (by Sheikh Hasina’s own admission, as told by her one-time aide Matiur Rahman Rentu).

On April 1, 1971, all newspapers of Pakistan flashed a frontpage picture of a pensive Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, surrounded by police escorts, at Karachi Airport. I am unable to find any explanation to this strange, rather unbecoming, conduct of a politician whom the Bengalis reposed their complete trust.

Today, many self-serving “pundits” give umpteen reasons why Mujib surrendered leaving the 70 million Bengalis at the gunpoint of Pakistani killers. They never touch the fact that his family was protected by the military that was making the rest of Bangladesh its “killing fields.” Some of these pseudo experts even thought it was Mujib’s “masterstroke of statesmanship.” If so, why he could not divulge it to his top aides like Tajuddin and Dr. Kamal Hossain?

The vast majority of Bangladeshis seek answers.

(The article is re-published from a earlier one.)

*R. Chowdhury is a former soldier and a freedom fighter in the war of liberation of Bangladesh. He enjoys retired life in reading, writing and gardening. He writes on contemporary issues of Bangladesh and has authored a few books.

March 26, 2023

The viewpoints expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the opinions, viewpoints and editorial policies of Aequitas Review.