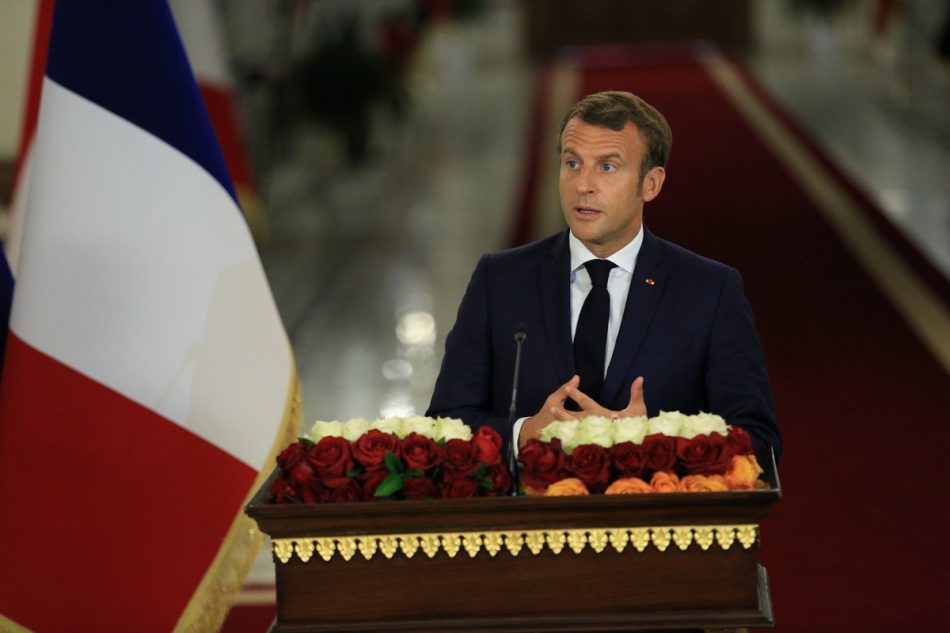

On October 2, the French President, Emmanuel Macron, delivers a speech to present his strategy for fighting separatism. He clearly targets (and stigmatizes) the Muslim community there (including 52 mentions of the words Islam, Islamism) insofar as it has refused to be assimilated (to cultural majoritarianism). But, this is a Muslim community which, as most social scientists admit, has engaged in an extraordinary process of integration, socially, economically, and to a certain extent politically, despite some cultural, urban and employment forms of discrimination against them.

While he acknowledged such discrimination and rightly cited the importance of training Muslim imams locally in France, he conflated religious extremism, political Islam, and Islam throughout. He, for instance, said, “Islam is a religion which is experiencing a crisis today, all over the world”. After the horrible terrorist act of killing Samuel Paty, a history teacher who showed his students cartoons that ridiculed the prophet Mohamad, Macron defended this as freedom of expression, saying: “We will not give up caricatures and drawings, even if others back away”. This indeed marks an entry into State Islamophobia, the phrase coined by Jean-François Bayard.

To understand his speech, one should read Emmanuel Todd’s recent Les Luttes de classes en France au XXIe siècle (2020). Here Todd makes it clear that Macron cannot secure a second mandate with the current erosion of his bourgeois and petit bourgeois social support as well as that of leftist leaning groups, especially in the wake of the Gilets Jaunes movement in France. He must therefore attract the classical electorates of the far-right identarian movement, National Front (especially the working class component). The strategy to fight separatism in these Islamophobic, populist, and arrogant secularist tones is indeed first and foremost an election strategy. In this article, I want to focus on how the populism of Macron conceptualizes freedom of expression and “political Islam” to this end.

Freedom of expression vs social responsibility

Freedom of expression, which is a basic human right, becomes unethical when intellectual rigor and social responsibility are lacking. Charlie Hebdo through its cartoon has incited Europe against Syrian migrants, even mocked the three-year-old Syrian boy Aylan Kurdi, whose body was washed up on a Turkish shore.

To present the Prophet Mohammad as a symbol of terrorism or sexual perversion, as is done in many published cartoons, is no different from presenting Prophet Moses as the symbol of right-wing Israelis’ actions against Palestinians, an association that would be rightly condemned as anti-Semitic, prohibited by the laws of many European countries. No Muslim leader has ever blamed Jesus Christ for the many atrocities that have been committed around the world in the name of Christianity, nor Buddha for the genocide of Rohingya people. The populist reductionism that lies behind these cartoons is embedded in the tradition of European antisemitism that began with the demonization of the Jews, their faith, and their culture and ended in the attempt at their extermination. Some argue that Charlie Hebdo statistically does not target only Islam as a religion. This is true, but the perversity and the systematic simplistic analyses portraying Muslims (because of their prophet and their Quran) as terrorists is nothing but populist.

Is blasphemy, introduced by the French revolution in 1789, a right in France? A universal value tout court? Shouldn’t we first see whether it entails incitement against a minority that has its own fragile status as citizens/migrants? Blasphemy is now hailed not just as a right but a kind of duty, as was clear from a TV interview in 2015 with Jamel Debbouze, a Moroccan-French comedian, who was pushed to blaspheme in order to show his assimilation to French cultural majoritarianism. In the words of Emmanuel Todd: “Yes, of course, there’s a right to blaspheme, but one must also have the right to say that blasphemy is not a priority and that it’s idiotic… I was demanding the right to counter-blaspheme: to say that the caricatures of Muhammad were obscene, rubbish, totally historically out of sync and the expression of rampant Islamophobia. And, for saying that, I was accused of complicity with the terrorists.”

In France, it is only cultural majoritarianism with its arrogant secularism, combined with the reminiscence of colonial imaginary that dictates the limits of freedom of expression. There, you go to prison if you question the number of Jews killed in the Holocaust or if you call for boycotting Israeli products. Macron repeated in many speeches that he equates anti-Zionism with anti-Semitism, i.e. calling for its criminalization. While I fully understand, by all the standards of social responsibility and intellectual integrity, the requirement to ban from the public sphere those who deny the Holocaust as a clear historical event, one should not criminalize historical discussion about historical details.

At the same time, President Macron, the ally of most of the Arab dictators (chiefly for economic reasons including selling them arms), joins the authoritarian choir which “juridically” seeks to ban what they lump in one category as “political Islam”. Currently, France is deploying its security apparatus to dissolve some of the Islamic NGOs and political entities deemed to fit this description.

Against “political Islam” or simply against an organized social movement

While many politicians and journalists, even some social scientists, insist on using the term “political Islam”, it hemorrhages meaning by not clearly demarcating the foundational differences between classical Islamism and neo-Islamism. It is a stereotyping generalization that does not account for the heterogeneity of Islamic political thought, from the moderate to the extremist, from that carried out by individuals to Islamic movements and to official Islam.

The term political Islam is often used to deride a movement and to suggest that all of their trajectories are the same, composed of readers of Sayyid Qutb of the Muslim Brotherhood and the proponents of al-Qaeda and ISIS. It is worth noting that in the Arab world among those who employ such categorizations are those ‘guardians’ of official-Islam who consider that the Islam to which they adhere is essentially apolitical. As such, the delegitimating by those guardians of the Islamic opposition in the religious sphere is a way of denying that they too are political.

In the Gulf monarchs, for example, any opposition figure is viewed as being part of the Muslim Brotherhood (this is how Khashoggi’s murder was justified according to some political statements and popular tweets in Saudi Arabia), and then considered as a terrorist. The Lebanese philosopher Karim Sadek has studied how one can understand the Tunisian leader of al-Nahda Rachid al-Ghannouchi’s liberal thought and policy by using Alexis Honneth’s theory of recognition. What Ghannouchi is asking for is the recognition of Islamic identity in the public sphere and recognition of the importance of religious texts, interpreted through ijtihad (innovation) and the concept of maslaha (interest).

Among the most important reformists in the Arab world today are figures from these neo-Islamic movements: Sheikh Ahmad al-Raysuni and Dr. Saadeddine Othmani. The former was the head of the Movement of Unity and Reform (MUR). He is currently president of the World Union of Muslim Scholars, and his innovative influence extends far beyond Morocco. Saadeddine Othmani has, since 2017, become the Moroccan Prime Minister. In the line of what is universal today in secularism, Othmani was the first to theorize clearly the distinction between politics and religion and between State institutions and religious ones, while connecting them through ethics. He constructed a theory differentiating between religious advocacy (da’wah) reasoning and political reasoning.

In a nutshell, Macron’s Minister of Interior, Gerald Darmanin, declaring a potential ban on the “Muslim Brotherhood” (MB) in France, and portraying them as more dangerous than Salafism, shows such a degree of bigotry and ignorance of the importance of such actors in potentially facilitating Macron’s very call – a just call – for an “Islam des Lumières” (Islam of Enlightenment). Anyone can consult fatwas and statements of the European Council for Fatwas and Research or the teaching of the European Institute for Human Sciences (both historically close to the Muslim Brotherhood) to see the huge difference between these and the teachings of any Salafist or traditionalist Islamic movements either in Europe or in Islamic countries.

This clearly indicates that Macron and his minister are simply banning those Islamic movements which 1) are politically highly organized, 2) refuse to call for assimilation to cultural majoritarianism, and 3) call, instead, not only for integration into French pluralistic society but for positive integration (i.e. being proactive actors as opposed to victimized agents). These actors, in line with similar ones in all religions, are extremely important in providing care, conviviality, love, hospitality, and communal solidarity in our individualistic capitalist world.

Again, I am not endorsing here any conservatism to be found in the existing MB social agenda, but stressing a differential analysis between this agenda and that of other forces. In any case, Macron’s call for “Islam des Lumières” cannot be set in motion by some anti-clericalist intellectuals, nor with some puppet Imams close to the French or North African intelligence services.

This so important top-down call needs a broad religious socio-political movement to carry it (bottom-up) while operating in a democratic and pluralistic political and social space. The most flagrant case is the attempt to ban The Collective Against Islamophobia in France (CCIF) which has won many court cases during the last decade. This is despite the fact that many social scientists in France have been using the word Islamophobia between quotation marks (i.e. “Islamophobia”) over the last decade, as if they did not believe that it constitutes a social phenomenon sufficiently dangerous even to merit a label.

Having said this, I am not unaware of the sensitivity that we social scientists who care about moral secularism, have towards the ambiguous and conservative social thinking of religious movements. But we cannot turn a blind eye to how they are changing and how their supporters formalize their judgments, evaluations, and justifications in their everyday life, beyond the religious reasoning and mono-universalistic and arrogant model of French secularism. A conservative “quietist” Wahabi Salafism, for instance, cannot be combated by any security apparatus, but only by a long process of dialogue and the use of the rule of law.

Peaceful coexistence

At a time when humanity is in dire need of understanding to ensure peaceful coexistence, the propagation of a set of ill-conceived drawings has reinforced ignorance and hatred towards Muslims, and incited, albeit inadvertently, violence against European citizens and their interests in Arab and Islamic countries. This is a trap that has been skillfully or stupidly set up by ‘neo-con’-style Charlie Hebdo journalists and endorsed by populist politicians. Alas! The consequence of Macron’s carnival of stupidity is this wave of barbaric killings that I have no strong enough words to condemn. All the arguments of this article should not be read as qualification my denunciation of these terrorist acts with “but”. I seek to understand the context of such conflicts and terrorism: they cannot be simply understood as nihilist acts.

In addition, our modernity has the merit of universalizing the claim to democratic pluralism which entails freedom of expression. The same modernity also introduced notions of tolerance (dear to John Locke), such as moral sensitivity and dignity. Yes, there are many occasions that oblige us to think twice before offending the dignity of the others for the sake of tolerance or conviviality. How do we bring all these things together? This will require sound moral deliberations, instead of using laws and human rights as a weapon in the hands of the strong. Cultural majoritarianism, i.e. a perceived superiority that reclaims arbitrary space and importance, is fundamentally in conflict with liberal democracy, pluralism, moral secularism, and even critical republicanism. (See Cécile Laborde Français, encore un effort pour être républicains!). For Mohammed Bamyeh, if secularization leads to more tolerance of diversity, then it also leads to intolerance of religion itself. That is, everyone in society is required to abide by some core (liberal) values, regardless of one’s religious belief, without any “reasonable compromises” a la Charles Taylor.

The serious challenge of our modernity is to combine the rule of law with the rule of virtue, as the latter needs constantly ongoing argumentation. As one of the producers of virtue, religion is always involved and seeks moral enforcement through rituals. Moral secularism and religious virtues – while they ascribe to different (theist or atheist) worldviews/ideologies, and enter into competition if not conflict with each other – should deploy a non-authoritarian practical reasoning, and pay attention to the borderline between critique and incitement to all forms of hatred.

*The writer is Professor of Sociology at the American University of Beirut and editor of Idafat: the Arab Journal of Sociology (Arabic).

(Open Democracy)

November 2, 2020

The viewpoints expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the opinions, viewpoints and editorial policies of Aequitas Review.