In the summer of 2007, when I spent many hours talking to presidential candidate Barack Obama about his view of world affairs, I was surprised to find that he looked to the administration of George H. W. Bush as a model of professionalism, prudence, and stewardship of American national interests. For all his own transformational impulses, he wanted to put together a team like the one led by Secretary of State James Baker and national security advisor Brent Scowcroft.

Unlike Bush, Obama arrived in the White House with scant experience in national security. He needed to demonstrate his seriousness. And so when it came time to choose his own team, Obama turned to a superstar, Hillary Clinton, for secretary of state, and to James Jones, an erudite general he barely knew, as national security advisor. Clinton turned out to be a fine choice; Jones was a disaster, soon replaced. Obama did finally put together the team he wanted, though it never meshed quite as smoothly as the Bush machine.

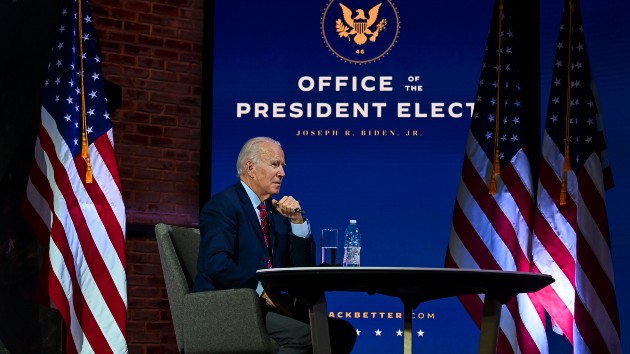

With the announcement on Sunday night that he plans to appoint Antony Blinken as secretary of state, Jake Sullivan as national security advisor, and Linda Thomas-Greenfield as United States ambassador to the United Nations, President-elect Joe Biden, who will be the first president since Bush Senior to arrive with deep foreign policy experience, may have built precisely the kind of team that Obama had in mind, and that national security professionals have been yearning for since the Bush era.

Professionalism is not, of course, a substantive point of view about the world. There will now be much minute parsing of texts for the views of these three figures, and of the others whom Biden has since named. Within hours of the announcement, I found in my inbox copies of Blinken’s recent discussion of foreign policy at the Hudson Institute and Thomas-Greenfield’s co-authored article on diplomacy in Foreign Affairs. Feel free to parse away; but don’t waste time looking for the eccentric apercu. The views you find will not stretch very far beyond the 40-yard-lines as they are understood in the Council on Foreign Relations and the other mainstream foreign policy think tanks.

The Biden team promises restoration, not transformation. Everyone hoping for sharp departures from the pre-Trump past—leftists like Bernie Sanders who recoil from shows of power, unreconstructed neoconservatives who have had it with “leading from behind,” astringent realists who believe that America has been on a reckless bender ever since the Berlin Wall fell—is going to be disappointed. Thomas-Greenfield and her co-author, William Burns, both career diplomats, write that a prudent foreign policy will reject both “the restoration of American hegemony” and “retrenchment.” That will be the Biden sweet spot.

A restorationist foreign policy does not, as I pointed out in my series on Biden’s likely foreign policy, mean a return to the status quo ante. The world has changed drastically since 2016. Biden’s team will have to stand up to new challenges from China and Russia, reaffirm the centrality of democracy in the global order, coordinate the global response to the pandemic, and forge long-term changes on trade, taxation, and regulation in order to create a more equitable global economy. My conversations with Biden’s key advisors left no doubt that they recognize the magnitude of the challenge.

What is to be restored, then, is not a set of policies but rather the actual practice of statecraft, which is the art of applying available means to desired ends. What was truly bizarre about outgoing President Donald Trump’s foreign policy, after all, was not so much the ends, some of them quite familiar, as the means chosen to achieve them, which could be explained only in reference to Trump’s own whims. Trump bargained with North Korea’s Kim Jong Un with no plan save to rely on his negotiating skills; he withdrew troops from Syria, abandoning our Kurdish allies, to curry favor with Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan; he proposed a “Middle East peace plan” designed to prop up Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu rather than actually create peace. His Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, stood by while Trump castigated, and then fired, the diplomats who told the truth about the secret policy towards Ukraine that got the president impeached.

Biden and his team certainly have a sense of ends, which have to do with restoring America’s moral, economic, and diplomatic leadership—American exceptionalism in a new key. Some of those ends will not differ very much from Trump’s; but they will choose means most likely to actually attain those ends. For example, both Biden and his chief advisors, very much including Blinken, have said time and again that the way to induce China to behave according to the rules of both global economics and state sovereignty is to act in concert with allies and to insist upon respect for the rule of law. That’s a pretty low bar, but it’s one Trump only rarely met.

Absolutely anyone Biden could have appointed to senior national security posts would have represented a return to normalcy. Yet the appointment of Blinken as secretary of state is revealing. Biden could have chosen a global celebrity like Hillary Clinton or John Kerry or Colin Powell who could stand as equals before heads of state. He could have chosen a wise old dealmaker like Warren Christopher, or even State’s senior-most diplomat, William Burns. But Biden doesn’t need those things; he already knows everybody.

Antony Blinken is family; he has been thinking, talking, and traveling with Biden for the last 18 years. What each believes is an extension of the beliefs of the other. I have known Blinken since 2009. He is a careful thinker with an even keel, neither unduly optimistic nor proudly tough-minded, in the manner of the hard-bitten realist. He does not feature in his own stories, and is very unlikely ever to upstage the president. He is, like his boss, an extremely decent person. He has a very pleasing, almost velvety voice, and an elegant manner. His French is perfect. Altogether, in fact, Blinken puts one in mind of “the Wise Men,” Robert Lovett and John McCloy and Chip Bohlen, the prep schoolboys and Ivy League chums who forged American foreign policy after World War II. He may, however, have some trouble locating the voice of authority suitable to a secretary of state rather than a senior aide.

Jake Sullivan is also family. Yet it was easier to imagine the discreet and finely balanced Blinken as national security advisor, and Sullivan as a kind of super-counselor-on-all-things. Sullivan ranges beyond the 40-yard-lines, on both foreign and domestic policy, and he has thought deeply about the connection between the two. Earlier this year he and economist Jennifer Harris wrote a piece in Foreign Policy arguing that for the last 30 years, grand strategy has depended on a neoliberal economic paradigm that has now exhausted itself. Thinkers on the left have looked to Sullivan to import their ideas into Biden’s world. That is not normally a job for the national security advisor. Yet Sullivan, like Blinken, is so close to Biden, and has such an important role in policy matters, that he may have a remit that runs well beyond the honest broker role of national security advisor.

I do not know Thomas-Greenfield. The U.N. position is often filled by a political celebrity like Bill Richardson, who served under President Bill Clinton, or an ideologue like John Bolton, Jeanne Kirkpatrick, or Andrew Young. Given that, at least skipping over Trump, you’d have to go back to Clinton’s first term to find two white men running State and the National Security Council, no doubt it was important to place a Black woman in a senior national security position. Yet Biden chose a professional diplomat—the first since John Negroponte, who served in George W. Bush’s first term as president. Since Biden, unlike Bush, plans to take the U.N. seriously—and thus has elevated the ambassador to Cabinet-rank—the appointment also constitutes a validation of the Foreign Service, which has been so mercilessly abused over the last four years.

It’s also worth noting that even a ludicrously partisan Republican Senate majority may find very little pretext to withhold nomination votes for either Thomas-Greenfield or Blinken (a consideration that may have helped rule out Susan Rice at State).

Unless the Democrats win both Senate seats in the Georgia run-off in January, Mitch McConnell will remain Senate majority leader, and he will do everything in his power to foil ambitious domestic legislation. Real change may have to wait until after the 2022 by-election. Foreign policy is different; it depends far more upon action by the executive branch than upon legislation. Biden and his team can do a great deal to restore America to that position between hegemony and retrenchment from which it can exercise leadership. They will be able to start right away.

*The writer is a regular contributor to Foreign Policy, a nonresident fellow at New York University’s Center on International Cooperation, and author of the book What Was Liberalism? The Past, Present and Promise of A Noble Idea.

(Foreign Policy)

November 26, 2020

The viewpoints expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the opinions, viewpoints and editorial policies of Aequitas Review.