In India, mosques have become symbolic battlegrounds for competing historical narratives, turning many of the buildings into sites of contention and flashpoints for religious tensions. In some states, the Hindu right has been claiming that these mosques were built over destroyed Hindu temples over centuries of Muslim rule.

The most recent target in this campaign involves the 16th-century Sambhal Mosque, also known as the Shahi Jama Masjid, in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh.

This Mughal-era mosque was given “protected monument” status in 1920 during British rule under the Ancient Monuments Preservation Act of 1904. This layer of protection was eroded when a petition was filed by Hari Shankar Jain on November 19, 2024, alleging that the mosque was built on the ruins of the ancient Harihar temple.

Jain, President of the Hindu Front for Justice, has been the lead petitioner in most mosque dispute cases in recent decades.

Following the petition, a civil court ordered a survey of the mosque, igniting an old debate about “reclaiming the Hindu past.”

During the second survey of the same site on November 24, protests erupted from local Muslims, who were accused of pelting stones at surveyors. In retaliation, the police opened fire that reportedly killed four locals and injured several others. The police denied these claims.

Renewed debate

This recent tragedy has reigned the debate about mosques as sites of religious dispute in India. Incidents have become more commonplace under the far-right Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government’s rule, demonstrating a broader pattern of stoking controversies about Muslim places of worship, primarily those holding historical significance.

Two years earlier, for example, tensions between Hindus and Muslims simmered over the origins of the Gyanvapi mosque in the UP that was constructed by the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb. He’s often (unfairly) demonised and derided by the Hindu right in its quest to present a flawed sense of Hindu “unity” against the Muslim “other.”

After decades-long legal disputes over Gyanvapi mosque, the Supreme Court in April ordered that both communities could worship within the mosque premises – limiting Hindus only to the cellar area and designating the mosque and the courtyard to the Muslims.

The decision was seen as a victory for the Hindu right, as the verdict soon opened a floodgate of petitions for access to other historically Muslim sites.

This strategy is the direct result of the allied public extending full support – physical, emotional, and ideological – to the ruling elites.

Remembering Babri

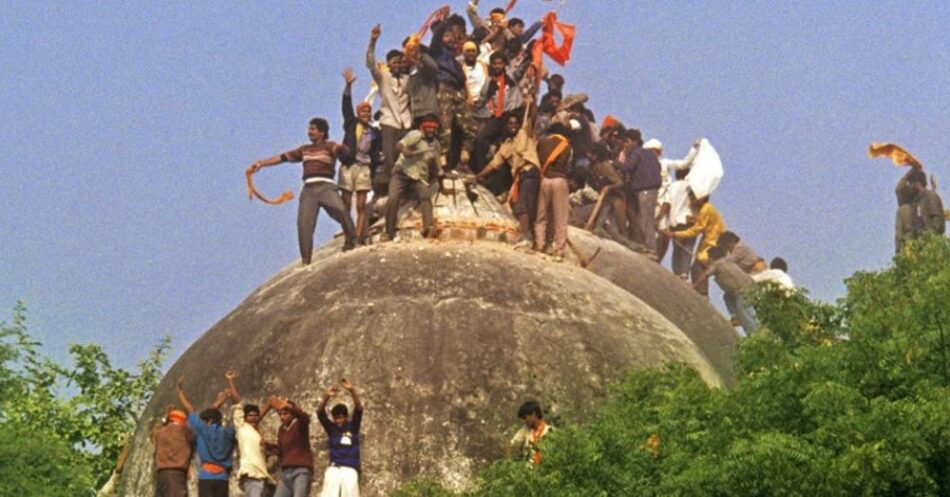

A cruel reminder of this is the legacy of the demolition of the 16th century Babri mosque more than three decades ago. On December 6, 1992, Hindu fundamentalists tore down the mosque on grounds that it was built by Muslim rulers on the ruins of an earlier temple, which they believe to be the birthplace of the Hindu Lord Ram.

This incident sparked rioting throughout the country. Almost 2,000 people were killed in the religious violence, mostly Muslims. The images and visuals of that violent episode were received like shards to the heart. This year’s inauguration of the Ram temple on the site of the razed mosque caused even more consternation to many.

As the current ruling party’s assaults on (Muslim) historical figures and magnificent structures become more fervent, it is the memory of the Babri demolition that haunts even today.

It is in this context of historical absurdity, and obscurantism that the past refuses to stay buried. It grips the present with an unrelenting onslaught on Muslim social life.

Notably, the BJP’s divisive politics go against the egalitarian principles of the Indian Constitution, which enshrines social equality and non-discrimination on religious lines.

Thus, the latest Sambhal mosque controversy reflects deeper tensions between the constitutional promise of religious freedom and the lived experiences of the community. It underscores the link between mosques and Muslim social fabric – as spaces of communal identity, solidarity, and cultural expression – becoming more than just places of worship.

Disputes surrounding mosques are framed by the Hindu right in terms of historical grievances and religious identity, making mosques powerful symbols of divisive politics in India.

Over the last decade, India has been witnessing a gradual and progressive decline and erosion of legal protections by the very guardians of constitutional morality, as the world watches idly.

Undermining legislation

It wasn’t always this brutal. But the seeds of dissension were sown by the Congress-led government, which permitted the opening of the gates of the Babri masjid in 1986.

Still, in 1991, India’s Parliament enacted the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, which froze the religious character of all places of worship as they existed on the date of independence, August 15, 1947.

The only exception was the Babri-Ramjanmabhumi dispute. With a clear intention of avoiding disputes over religious places, the act explicitly prohibits the conversion of any religious place to a different religious denomination.

However, former Chief Justice of India DY Chandrachud undermined and diluted the essence of this landmark legislation while hearing the Gyanvapi mosque dispute in 2022, observing that the 1991 Act did not disallow “ascertaining” the religious character of a place of worship, as long as there was no intention to alter its nature.

This observation by the Supreme Court opened the floodgates, creating new disputes and raking up old controversies about the status of religious sites. It also created a legal pathway for courts to allow and initiate inquiries into the historical religious character of a place of worship.

The simmering Sambhal issue is a result of this legal precedent that has set off a series of such claims and disputes.

Knock-on effect

One such development that took place in the wake of Sambhal controversy is the Hindu right’s claim over the 12th-century shrine of Sufi saint Khwaja Moinuddin Chisti in Ajmer city of Rajasthan – a site symbolizing syncretism and religious diversity.

Late last month, a local court in Ajmer issued a notice to authorities at the behest of a plaintiff, claiming that a Hindu temple existed at the site before the Sufi shrine was built. Popularly known as Ajmer Sharif and revered by Muslims and Hindus alike, the dispute over this holy shrine has sparked a debate over deepening divisions and fears of violence.

The deliberate move by the highest court of law has paved the way for historical revisionism and communal discord, rupturing the already fraught relations between the two communities.

At the heart of these religious contestations are the Hindu nationalist forces that are on a rampage to reimagine, reconstruct, and reclaim “their” past.

With no grounding in Indian history, the Hindu nationalists construct a fabled (Hindu) past – a singular history of oppression by Muslim rulers – while ignoring and actively erasing the Muslim past that bears witness to harmonious Hindu-Muslim relations in matters of statecraft, cultural expressions, and spiritual life.

The swift erasure of this complex and layered history aids the Hindu right in furthering ahistorical obscurantism that presents selective historical “facts” either of dubious reliability or an utterly prejudiced reading of history. This is done with the sole aim of promoting a linear history of Hindu-Muslim relations, which is tied to the quest for power.

This hankering for power is determined to destroy everything that comes in its way and rebuild a compliant society of collaborators in state excesses – whether through active participation, silence, inaction or indifference.

With normalisation of political marginalisation of Muslims in India, along with the manipulation of historical records, the suppression of culture and the destruction of heritage, the social death of Muslims is imminent.

On a ruminative note, one is compelled to ask, in the pursuit of Hindu glorious past, what are we risking as a nation? Are these early warning signs that go unnoticed, or have we crossed the point of no return?

*The writer is an Associate Professor at Jindal School of International Affairs in O.P. Jindal Global University, India. She did her PhD on Women in Tabligihi Jama’at from Centre for Political Studies, JNU. Her research area is Islam, Gender and Conflict.

(TRT World)

December 12, 2024

The viewpoints expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the opinions, viewpoints and editorial policies of Aequitas Review.