(A translation from the original Bangla of Enayetullah Khan)

“His strolls around the corridor of power at times drew pity; he frowned at straight talk; he tried to destroy a dissident with his wrath. He loved the nation, yet he betrayed it. He had to pay with his life. August 15 was the accumulated wrath of the people.”

A Short summary

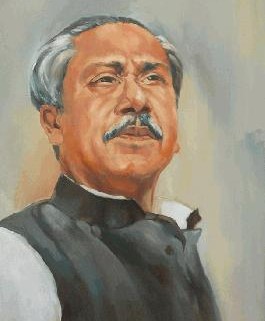

According to Enayetullah Khan, renowned intellectual and journalist (later ambassador and minister), Sheikh Mujib’s “political activities had dramatic excellence, but they were also tainted with his dubious characteristics.” He was a puppet at the hands of Indo-Russian expansionism. Like a true stage actor, Mujib followed their script with his skillful oratory and bluffed the people with a rosy future. His masters gave him the Peacock Throne but no power. Being a mortal, Mujib tried to play God but had no worshiper; nor could he symbolize the Lion of Judah. “He could not bear the burden of the crown he wore and went down under its weight.”

Like the heartless, ruthless king in Rabindranath Tagore’s “Roktokorobi,” he tried to build a self-serving dictatorial fiefdom over the sacrifice of the people in the liberation of Bangladesh.

People had trusted Mujib to bring freedom. But he betrayed them. Because, he had to repay the debts to his masters. The repayment included eliminating political opponents, banishing democracy, denying human rights, brutal repression, gagging the media, banning freedom of expression and sending 62,000 patriots to rot in jails. Mujib’s three-year rule broke hearts of thousands of mothers, bled hundreds of patriotic heroes, created new history in smuggling out national resources, destroyed the beauty and culture, and above all, sold out the national sovereignty. And the economy left nothing in the coffer. That was a tragedy! August 15 was the accumulated wrath of the people.

Placing the anti-national activities in a historic context, Khan traces them from the Agartala Conspiracy and efforts to thwart various popular national uprisings (as in 1969). As part of this exercise, India created the alternative forces of Mujib Bahini and Kaderia Bahini in 1971 to control the exiled government and channel the liberation war to serve its interests. The act continued in independent Bangladesh with Mujib as the Indo-Russian surrogate. The One-man, One leader, one country mantra of “Mujibbad” was developed to create a dynastic cult. The final act of the play came in the form of the One-party rule under “Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League (BAKSAL)”. The role and objective of these external masters were no different from the extorting business of the East India Company in the eighteenth century.

The history was distorted. The sacrifice during various movements, as well as in 1971 was made by the common Bengalis, and certainly “not by a man, nor by a coterie.” The country belonged to all patriots, Khan asserted.

Mujib’s dream was to be an all-powerful king. Enayatullah Khan thought that Mujib’s obligations with his masters and non-achievement of his objectives were manifested in his outbursts of favoritism, egoism and display of excessive self-prowess. The more he got himself entangled with the strings of desire, the more he grew disenchanted with delusions, a state of paranoia.

That Mujib had no free hand was evident during a personal encounter by Khan. After Khan was released from jail, he met Mujib on July 29 (1971). “I am sorry for what happened to you, but my hands were tied,” said Sheikh Mujibur Rahman amidst restless pacing.

“Therefore, if we cannot defeat bad politics,” wrote Khan, “if we cannot jump into the struggle to break the shackles of slavery, and if we cannot unite the patriotic and progressive forces of intelligentsia and the people from all walks of life, the country will fall again into a puppet regime.”

(The country, in fact, has been groaning since 2009 under the puppet regime of daughter Sheikh Hasina: like father, like daughter. —Translator)

“Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was a Greek tragic character,” concluded Enayetullah Khan, “who suffered from a narrow class complex, had great love but was a weak human being. His strolls around the corridor of power at times drew pity; he frowned at straight talk; he tried to destroy a dissident with his wrath. He loved the nation, yet he betrayed it. He had to pay with his life.”

Rise and Fall of Sheikh Mujib

By Enayetullah Khan

I would be wrong if I say I was shocked at the untimely fall of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. But I might have been surprised at the suddenness of the event. Even in my dislike of the man, my heart ached. Unnecessarily I kept worried about the future. But these are my personal political thoughts, natural to a middle-class mentality. My immediate despair was of relief. The bell rings of a bright distant future awakened my constricted notion.

These words are sad, rather rude, but pure truth. Truth comes out of natural justice, and in the course of history. The differences between these two are original. First is culture and the other is science. One may say inevitable while the other may call dialectic. But both have the inescapable end. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s politics, ascendance to state power and the fall from grace is the tragic end of this natural phenomenon.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s political activities had dramatic excellence, but they were also tainted with his dubious characteristics. In the past decade, his rise to power was meteoric; it had the combination of sacrifices and myths. His tale of kingship combines a towering personage and appearing at the right time of history.

Roktakarabi

His was a fairy kingdom. He could not bear the burden of the crown he wore, in fact, went down under its weight. As the king of ‘Roktakarabi’, he tried to establish a self-serving dictatorial fiefdom. He did not care for the dead, nor those who rejected the conspiratorial politics and took up arms to liberate the motherland. Instead, on their sacrifices, he tried to build for himself a mythical powerhouse, where there is one God but no worshiper. Ignoring the common people, he played a divisive political game. Outsiders (foreigners) made Sheikh Mujibur Rahman their puppet king.

I know my narratives are sad, but history is merciless. August 15 is the direct example. The silence of the dawn was broken by gun blasts. As if carrying the wrath of millions, a sudden brush of bullets felled the puppet kingdom. The story of this puppetry was not detached from the history or politics. Connected with it were greed for power of a coterie, as well as the schemes for imperialism and socialist expansion.

It was a strange story. In 1971, when 75 million people stood against the communal discrimination and deprivation, there continued a game of compromise behind their back. These local reactionary conspirators and some outside forces had earlier tried to thwart the mass uprising of 1969 and later the people’s resistance of 1971. But history did not remain standstill and watch the rulers to control its course. Despite evil efforts to create misunderstanding against national freedom, there came a popular resistance movement. The sacrifice on the night of March 25, 1971 was made by the Bengalis, not by a man. It (the country) belongs to all patriots, people from all walks of life have a share in it. And certainly not to a certain coterie.

To the contrary, a man or a coterie obsessed by its obsolete political profiteering, had tried to stop the popular resistance movement, even by sacrificing tens of thousands ordinary people at the altar of its greedy power game. The barricades in Chittagong, the military revolt in Joydevpur, the revolutionary gathering in Pabna, the historic resistances in Comilla and Brahmanbaria nullified the secret negotiations at the presidential palace and created the grounds for mass revolution. But the self-seeking leadership ignored the blood of heroes and engaged in divisive politics at the round table.

Last call: Hartal, not the Liberation War

As such, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman could not make up his mind even on the evening of March 25. His last call was the Hartal (stoppage) on March 27 (1971), not the liberation war. At that critical juncture, the military and the revolutionary youth took the lead and started the resistance war. Yet, that war could not take the shape of a complete people’s war (for independence). Because an external power (India) was determined to channelize the conflict to serve its own interests. It formed the so-called Mujib Bahini to create division and confusion within the Mukti Bahini (Liberation Forces). And(finally), came the direct military intervention to thwart or mislead the popular war.

The history of this plot is long. When the heroic fighters of the Mukti Bahini, its young guerrilla groups and its revolutionary fighters inside the country, were at the doorstep of reaching their goals, Mujibnagar’s central political leadership hatched the conspiracy. The scheme was to control the war and rehabilitate the rejected leaders. Whoever tried to challenge this course of action, were politically condemned with disinformation.

The late Durga Prasad Dhar (D P Dhar) virtually ran the dynastic Mujibnagar government (Bangladesh Exile Government). Their creation of Mujib Bahini, also a dynastic expansionist element, and its counter-revolutionary activities were the worst chapter in the liberation war. History bore its witness. Millions of freedom-loving and anti-expansionist people would testify to it. We saw its (the plot’s) result on December 16, 1971.

The people of the country received a puppet government in exchange for three million lives and their sought-after goal of national liberation.

Mujib bahini to Mujibbad

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was the principal character behind this history. The notorious Agartala Conspiracy Case and the Mujib Bahini of 1971 were not separate from each other; they are parts of the same chronicle of the story of separatism. The struggle of seventy-five million Bengalis was against their neglect and suffering. It had a fundamental difference from imperialism, expansionism or bourgeois struggles. First and the worst was the Bengali bourgeois class, spineless but power-greedy middle class. Second, the desire for political and economic freedom for the entire Bengali as a group. Perhaps my heartburn was more because despite enjoying the complete support of the entire nation, Sheikh Mujib could not come out of his narrow class complex and from the shackles of his foreign masters. Rather, he willingly or unwillingly played the dubious role of a protege.

But he (Mujib) was a shrewd actor. With cunning moves at every situation, the stage politician acquired accolades from the public. His oratory skill and dreamy presentations (of the future) mesmerized the audience. People gave him the crown seeking national independence. But in the process of repaying the debts (to foreigners) of earlier conspiracies, he betrayed the trust of the freedom-loving Bengalis. That was a tragedy for him.

Even his absence (during the war) did not stop the game of the groundwork laid out by him. Carefully crafted counter-revolutionary force of Mujib Bahini continued to play the Machiavellian role on his behalf. This conspiratorial alternative force adopted Mujibbad as its weapon, philosophy and ideal. The naked distortion of the movement of language and democracy was part of this scheme.

The history of Mujibbad and Mujib Bahini is not yet spelled out. But this counter-revolutionary organization and its Mantra, aided by an external authority, was not only meant to establish an autocratic rule in the country, but also to ensure the hegemonic and expansionist control of that outside country (India). The creation of Rakkhi Bahini in the post-independent Bangladesh is the reincarnation of Mujib Bahini and Mujibbad.

The creation of Mujibbad and Mujib Bahini had multiple objectives:

a. To check the growing strength and influence of the Mukti Bahini, if the liberation war lengthened.

b. To face the patriotic and revolutionary social forces of the wartime guerrilla fighters.

c. If needed, to take over the county in Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s absence.

Because of the first two, there were serious conflicts of interest between the Liberation Forces and the Mujib Bahini. The third also created conflicts between the Mujibnagar government and the agents of expansionism (India).

The creation of an elite force with explicit intentions had more background stories. According to some Mujib Bahini leaders, their forces were created by Mujib’s chosen leaders which he had given in a handwritten letter. It may be mentioned here that this Dehradun (India’s military training complex) trained counter-revolutionary force was not part of the liberation force headed by General Osmani. Nor was it under the control of the government of Tajuddin Ahmad at Mujibnagar. Organized under the direct stewardship of an Indian general and the political objectives, the setup and its historic background proved, without any doubt, that this so-called Mujib Bahini had a fundamental difference from the national independence movement. I had earlier mentioned those as the possible reasons for the clash of interests between the exiled government and external interests. If Sheikh Mujib’s letter was true, it also proved that Mujib Bahini had a deep correlation with the Agartala Conspiracy Case.

Followed predetermined script

Unfortunately, though, the truth was that Mujib’s role was predetermined. Like a true stage actor, he followed the script of the director (external agents) to the hilt. (By default), people made him a fairy tale hero; he became the prince of fortune. But his glass house of fortune, his Achilles heels, collapsed in a painful moment on August 15.

It may also be noted here that the conflicts between the Mujibnagar government and the Mujib Bahini and the so called Kaderia Bahini had no connection with the independence struggles of the Bengalis. This conflict was for capturing the throne. The uncertain future of the liberation war, fear of its prolongation and the uncertainty of Mujib’s return to the country intensified this conflict. However, Mujib’s return ended that conflict, because Mujib was the main character and tool of the foreign agents. The fairy hero kept beaming within his dreamhouse. The myth of his self-generated sacrifice, and above all, his overbearing personage and historic past served to be effective in creating misunderstanding within the national independence struggle.

Mujib’s (fake) display of love for the people was a color screen of his class character. Yet, he was the ideal representative for the spineless bourgeois group.

Story of this stringed doll-dance, in other words puppetry, was strange. Obviously, as this class of non-productive, grab-all and defeatism were to remain solely dependent on the script they play, meaning the masters behind the scene: the forces of imperialism, social and cultural expansionism. In the historic context of the sub-continent, these masters continued to exert control on the middle-class power elites of Bangladesh to remain dependent on them.

Dependence on India and Russia

In the past three and a half years, the pillar of this foreign dependence was the hegemonic India and socialist Russia. They determined the rules for Bangladesh’s political, administrative and economic systems. Thus began the second chapter of the scheme, — by trampling people’s aspirations, by sacrificing national sovereignty, by destroying the economic goal of development, and finally by ignoring national education and culture at the behest of these outside masters. The outcome came to be known as, One Party, One Leader, One Country. And, the country soon landed in political, economic, social and cultural bankruptcy. The end result was a looted, destroyed and ruined Bangladesh.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was the powerless lead character in this game. I had witnessed his despair. I saw the fruitless wailing of the bonded multitude. Here was his dubious nature. He was the make-belief, mythical king. His political activities had full of contradictions. He had to keep repaying the debts to his masters with interest in a geometric progression. His only return was the Peacock Throne of Power.

I invoked the lengthy discussion only to highlight one point. In Bangladesh’s social structure, social divisions and in its historical context, one person’s weakness or one person’s failure in management or the corruption of one person or a group or the administrative stalemate cannot be the sole reasons for the fall of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

Dream of all-powerful king

Because, history and politics move at its own pace, where the person is minor; the dynamics of the events is main. Sheikh Mujib’s rise and fall were the result of those events. His dream was to be an all-powerful king. His display of favoritism, nepotism, sky high ego and self-esteem were aggressive outbursts of his personal and group bondage (with external thread) and non-achievement of his objectives. The more he got himself entangled with the strings of desire, the more he grew disenchanted with delusions, what we call ‘paranoia’ in English.

After I was released from jail, I met him on July 29 (1971). “I am sorry for what happened to you, but my hands were tied,” said Sheikh Mujibur Rahman amidst his fugitive pacing.

Despite knowing the duplicity in his character, I believed him. Because, I knew playing a political proxy was sad, in which the actor could play the role but cannot run the show. The masters gave him the pride but no life. He got the costumes but no independence. One Leader, One Party was the last part of this pantomime play.

For the past three and half years, the poor people of Bangladesh were the silent spectators of this grand mime play. Their silent cries met with laughter and cynicism from the perpetrators and their behind-the-scene coterie of conspirators. This coterie came in the guise of friends under the cover of globalism only to engage themselves in conspiracy to turn Bangladesh into a playground to serve their interests.

BAKSAL

The spineless ruling class ruined the country’s economic and social foundations by patronizing and servicing the investments of the external masters. Their blueprint finally took the shape of one-party (BAKSAL) rule.

As a result, Bangladesh turned into a ground of influence of the socialist world in one hand, and an almost colonial hinterland for the collapsing industries of eastern India on the other. Such examples of planned destruction of a country’s productive force were rare in the twentieth century. It can be compared with the looting (extracting) business activities (in India) of the East India Company in the eighteenth century.

These dual forces, at times alone at times jointly, still continue efforts to establish their political and economic interests in Bangladesh. To control the domestic politics and economic activities, as well as to force surrender the national sovereignty to outside masters, these external forces introduced the idol-worshiping (cult!) in politics. They presented the philosophy of Mujibbadi fascism in that cult. In this exercise, the two other patriotic, but externally guided, political forces (Communis Party of Bangladesh-Moni Singh and National Awami Party-Muzaffar) joined Mujib’s Awami Leage).

One Leader, One Part was not Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s lone thought process. It brewed from the consequence of loss of patriotism in politics over the past three and a half years. As such, its fall cannot be attributed solely to random corruption, loot, maladministration, nepotism and dynastic rule. The reasons were in the political history of the country, as explained above.

I am returning to the same issue again and again, because in my view, politics is the main, not the person. History is important, not the characters. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was not the Lion of Judah; nor was he a divine character. He was a common mortal, born and brought up in Bangladesh society.

To me, analysis centering around a person is anti-politics and faulty. He was the medium, central character, under whose leadership grew the real bourgeois class and its vast fiefdom. The socialist and expansionist forces always depend on these self-seeking middle classes to serve their masters’ interests. That was how those external forces succeeded in establishing themselves in Bangladesh riding on the shoulder of the man (Mujib) under discussion.

The lowest cadres of the Bangladeshi bourgeois class ran the administration, and this bureaucratic group was the worst corrupt loyalists of the regime. The local agents of the profiteering external investments became the most powerful in the economic circle.

Debt payment!

As leader of these slavish lackeys, Sheikh Mujib paid back the favor within a year in exchange of his power and position. The payment included killing democracy, brutal oppression, banning freedom of expression and killings. Even now, 62,000 political workers, revolutionaries and freedom fighters are rotting in jail and awaiting release. They were earlier thrown in by Sheikh Mujib. Supporting and rejoicing in such acts (of Mujib) was a derailed parasite group identifying themselves as communists. Because until the patriotic and revolutionary forces are totally eliminated, their (communists) objectives could not be achieved.

Sheikh Mujib’s three-year rule broke hearts of thousands of mothers, bled hundreds of patriotic heroes, created new history in smuggling out national resources, destroyed the beauty and culture, and above all, sold out the national sovereignty. And the economy left nothing in the coffer.

Therefore, if we cannot defeat that bad politics, if we cannot jump into the struggle to break the shackles of slavery, and if we cannot unite the patriotic and progressive forces of intelligentsia and the people from all walks of life, the country will fall again into a puppet regime.

Finally, I will say that Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was a Greek tragic character, who suffered from a narrow class complex, had great love but was a weak human being. His strolls around the corridor of power at times drew pity; he frowned at straight talk; he tried to destroy a dissident with his wrath. He loved the nation, yet he betrayed it. He had to pay with his life.

Bangladesh Zindabad! Long live our independence.

(Source: Bangladesh: 1972 to 1975, edited by Muniruddin Ahmad. Novel Publishing House, January 1989)

[1] Excerpts taken from the book A Soldier and the War Within: Post-Independence Bangladesh, Amazon, 20222. Renowned intellectual and journalist (later ambassador and minister) Enayetullah Khan wrote it for the Weekly Bichitra, which was published it in October 1975.

*The writer is a former freedom fighter of Bangladesh in 1971. He has authored a few books and co-authored few others. He regularly writes on contemporary issues of Bangladesh.

September 23, 2023

The viewpoints expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the opinions, viewpoints and editorial policies of Aequitas Review.