The reasons are not far to seek.

M M Azizul Haq wrote “Indemnity Rohit: Kar Sarthey? (Repeal of Indemnity: In Whose Interest?)” in the Daily Inqilab on November 1, 1991. It was written in the backdrop of then opposition Awami League’s pressure for the repeal of the Indemnity Act.

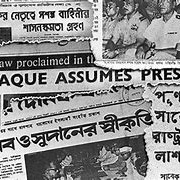

The new president (Khandokar Mushtaq Ahmed) promulgated an Indemnity Ordinance to immunize those who were involved in the military action on August 15, 1975. The ordinance became part of the constitution as the Indemnity Act in 1979 under the Fifth Amendment.

Azizul Haq gave the detailed reasons why August 15 took place, and what might have been the scenario in Bangladesh had there not been this coup, which was also called a revolution. The picture he painted was scary. According to most analysts, August 15 was inevitable. It was the call of the time, the call of the majority Bangladeshis who were groaning under the dark and heavy pressure of Mujib’s repressive machinery. If anyone was responsible for August 15, it was Sheikh Mujib himself. He invited it.

Love turned into hatred

Few leaders in history received so much love, such adulation and such welcome as did Sheikh Mujibur Rahman on January 10, 1972, upon landing in independent Bangladesh from his Pakistani shelter. He was still their hero, their “Bangabandhu.”

Few in the crowd then knew how Mujib tried till the last moment to save the unity of Pakistan, how eagerly he desired to occupy the seat of authority in Islamabad, how he dismissed Tajuddin Ahmad’s repeated plea to declare independence on the night of March 25, 1971 (Please see Tajuddin Ahmad Neta O Pita by Sharmin Ahmad, 2014, pp 59,60,148). Worse of all, how he quietly surrendered to the Pakistani junta thinking of the safety only of self and his family. The seventy million Bengalis who reposed their trust on him did not figure in his thoughts. They were left at the gunpoint of the marauding forces. Behind the surrender, another factor perhaps worked in his mind: avoiding an impending liberation war, which he never wanted. Bangladeshis would soon discover the real Mujib and turn their love into hatred.

Bangabandhu became Banga-Shatru?

Well-known Indian journalist and writer Khuswant Singh wrote in the Illustrated Weekly of India about Sheikh Mujib, “In 1970 he (Sheikh Mujibur Rahman) was the most-loved man by his people, and millions of others in India and elsewhere. Within a couple of years, he had lost much of his charisma and lived in a cocoon of self-spun esteem. He came to regard honest critics as traitors, and sycophants as loyal friends. It was a classic case of folio de grandeur. He was blissfully unaware that the very people who called him ‘Bangabandhu’ or ‘Bangapita’ to his face were behind his back called him ‘Banga-Shatru (enemy of Bengal)’”

In his book A book, a coup, some thoughts, former Ambassador and Secretary to the Government Syed Muhammad Hussain wrote about Mujib, “The smoke from his most expensive brand Erin pipe tobacco created a veil across his eyes and his senses, and he could not see for himself, nor were his ‘honorable’ bandoleers honest enough to keep him informed about the people and about their ever-growing problems and the rising tide of disenchantment through deprivation, neglect and unkept promises.”

Banglar Mir Jaffor

On January 2, 1973, Mujahidul Islam Selim, Vice President of Dhaka University Central Students Union (DUCSU), at a Paltan rally in Dhaka, withdrew the “Bangabandhu” title given to Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and canceled his life-long membership of the DUCSU, publicly tearing off the page from the register. It was the same student leader who granted him the DUCSU membership a year ago. Selim had further asked all offices to remove the pictures of Mujib. Among other slogans at the rally, “Banglar Mir Jaffor: Sheikh Mujib, Sheikh Mujib (Sheikh Mujib, the Traitor of Bangladesh) was the loudest. Motia Chowdhury, a fiery leader of the Students Union and later National Awami Party (Muzaffar), desired to make shoes and dug-dugi (hand-held drum), with the back skin of Mujib. “From today,” she declared, “you are no more Bangabandhu. You are Banga Satru. So said Shahriar Kabir, today’s Awami intellectual, “Mujib, you are no more Bangabandhu, you are Mujib, the National Betrayer.” (Ref: The Dainik Songbad January 3, 1973).

Muldhara Bangladesh (www.muldharabd.com) compiled a comprehensive list of political and social repression committed in 1972-1975 that went a long way to demonstrate that August 15 was a much-desired outcome.

Younger generations need to dig the media archives and familiarize themselves with the Bangladesh of 1972-1975, the supposed “Golden Period” of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. Those who lived the time needed to take a walk back for re-orientation.

Bottomless basket

The New York Times, the Washington Post, the Guardian of London, the Far Eastern Economic Review, and many other international media houses highlighted Mujib’s highly corrupt administration, under which 1.5 million people perished in the man-made famine of 1974 and its aftermath. Men and animals struggling for eatables in the city wastes were common sights. Poor women could not come out in the open as they did not have much to cover themselves. Dead bodies had to be buried with banana leaves. These are not fictional stories. These are no fairy tales. These were facts of life. One may check the pages of newspapers of the time.

But there was no dearth of relief goods, which remained hoarded in the warehouses of the ruling coterie, to be dispensed on political expediency or sold in the black market. Corruption and inefficiency of Mujib’s Bangladesh earned it the title of “International Bottomless Basket Case.”

To contrast the hungry and emaciated multitude dying in the streets and countryside, Mujib celebrated marriages of his sons– Sheikh Kamal and Sheikh Jamal–in royal style at his official residence Gonobhaban in July 1975.

So was Mujib’s birthday in March the same year. Official notices were sent out in advance to all offices, organizations, and establishments to “celebrate the occasion” and present themselves before the “god” to pay their homage. I recall watching the ceremony on the television screen how the processions paraded in front of the 32 Dhanmondi house, on the balcony of which the god took salute. On that day of heavy downpour, ladies in rain-soaked saris and salwar-kameez presented an unpleasant sight. For, few could dare to face the consequences of a no-show.

Rakkhi Bahini: The killer machine

Mujib’s personal force of Rakkhi Bahini killed more than 30,000 political opponents. Enayetullah Khan of the prestigious The Holiday put the figure at 38,000. A S M Abdur Rob of Jatiyo Samajtantrik Dal (JSD) claimed that over 40,000 of his cadre were killed/disappeared during that period. Mujib himself bragged on the parliament floor the killing of Siraj Sikdar, a top leftist leader.

Can one imagine how many additional lives would have been lost had there not been August 15?

Emergency

At the end of 1974, Emergency was clamped in the country. Fundamental Rights were suspended. Publication of all but four government-controlled newspapers was canceled. Political activities were banned. Anyone not toeing the official line was either in jail or not seen again.

As if he did not have enough, Mujib made a no-debate, eleven-minute constitutional coup on January 25, 1975, to make himself the omni-powerful President, showing the exit door to the sitting president Muhammad Ullah. In addition, he re-designated himself the “Father of the Nation,” a nation that he never wanted. The New York Times of January 26, 1975, termed it a “death knell on the nascent democracy in Bangladesh.” Reportedly, there was a plan, through the Awami Chatra League route, to make Mujib a Lifelong President.

BAKSAL

The last nail on the dying nation was hammered in the form of Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League (BAKSAL), Mujib’s supposed Magnum Opus. BAKSAL was a socialist inspired one-party government. All other political parties were squashed. The military and the bureaucracy were politicized by forcing them to join it. The country was divided into 61 political districts, each to be administered jointly by a BAKSAL governor and a BAKSAL Secretary, chosen personally by the leader. The system was to take effect on September 1, 1975.

Noted historian and author K Ali wrote in the New Nation regarding Sheikh Mujib, “He was out and out a despotic ruler and snatched away fundamental rights of the people by introducing absolute dictatorship under a one-party system–there was hardly any doubt that the measure (one-party rule) was taken only to establish his permanent rule in the country without any opposition.”

Yet, Mujib’s daughter Sheikh Hasina and Mujib sycophants think he was a god, who single handedly fathered Bangladesh and filled it with gold!

[1] Taken from the book A Soldier and the War Within, Amazon, 2022.

The writer is a decorated freedom fighter of Bangladesh and an accomplished author.

August 15, 2023

The viewpoints expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the opinions, viewpoints and editorial policies of Aequitas Review.