As funeral pyres burn in the streets and hope diminishes, India is reeling from a deadly wave of COVID-19 cases.

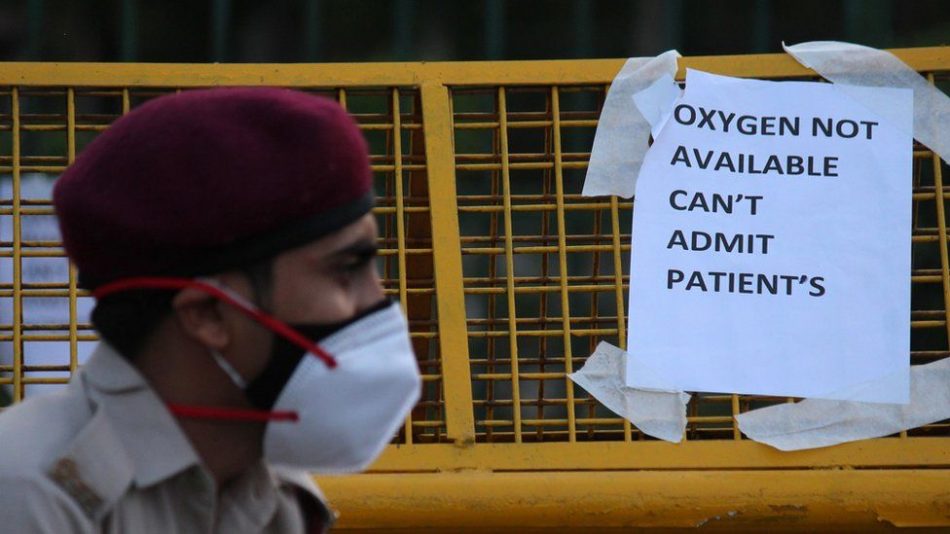

With 314,835 new COVID-19 cases recorded yesterday – the highest one-day increase in cases globally – the cracks within India’s frail healthcare system have been laid bare. A tally shared by the city government indicated that six hospitals in New Delhi had run out of oxygen. Desperate civilians took to Twitter to try to access oxygen supplies for their relatives through the #IndiaNeedsOxygen hashtag.

Meanwhile, in Brazil, local media have reported that hospitals are being forced to intubate COVID-19 patients without sedatives and the country reported 3,560 COVID-19 fatalities in the past 24 hours.

Critics of India construct a picture of complacency, both within Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist Government and beyond. Last month, thousands of citizens filled a new cricket stadium, named after Modi himself, to watch matches. Last week, millions of devotees – supported by ministers – gathered for the Kumbh Mela, a religious festival on the Ganges river, traditionally seen in India as a symbol of hope and purity. Masks were noticeably absent. According to local media, more than 1.700 people tested positive for COVID-19 in five days.

Throughout the Coronavirus pandemic, Modi has largely continued with election rallies and expressed his pleasure at the sight of “huge crowds” in West Bengal last weekend. Reports of a new Covid variant have since emerged but, despite this, a member of Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) told BBC’s Newsnight yesterday that cases of oxygen supply running out were simply a “one-off” (while more than 99% of all intensive care beds are full), religious gatherings involving millions of people have been taking place for centuries, and that the spread of the virus does not derive from them.

Yet, the future of India did not look as bleak as it currently does. At the end of January, the country basked in the assumption of success. A mood of euphoria emerged as Health Minister Harsh Vardhan asserted that “India has successfully contained the pandemic”. Months later, in Nagpur, the rate of intensive care unit patients, at 353 per million, is higher than anywhere in Europe. In Uttar Pradesh, there is a queue of more than 50 patients per hospital bed.

India’s lack of preparedness is rooted in years of neglect of medical infrastructure. Every doctor in India caters to at least 1,511 people, higher than the World Health Organization’s norm of one doctor for every 1,000 people.

There is now a bitter irony in Modi’s argument that India would serve as “the world’s pharmacy”, as hospitals across the country report a shortage of beds, oxygen cylinders and drugs and the country freezes vaccine exports.

“Just a little flu”

With a Coronavirus death toll of more than 380,000 people– the second-highest in the world – Brazil has the highest number of confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Latin America, surpassing 14.1 million.

Blinded by arrogance, Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro claimed that “because of [his] background as an athlete, [he] wouldn’t need to worry if [he] was infected by the virus” last year.

A month later, the UK’s Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab echoed this idea, claiming that Boris Johnson would overcome the virus by virtue of being a “fighter“. Former Prime Minister David Cameron – now at the center of the lobbying scandal – said at the time: “Boris is a very tough, very resilient, very fit person… I’m sure he’ll come through this.”

Dismissing COVID-19 as “just a little flu”, Bolsonaro advocated for Brazilians to go back to work, citing the economy as a greater priority over lives. When asked about the Coronavirus, Bolsonaro told local reporters that “I’m sorry, some people will die, they will die, that’s life” with palpable indifference, labelling state governors and mayors who imposed lockdown as “tyrants”.

Echoing the behavior of Modi, and continuing his opposition to social distancing, Bolsonaro – as an archetypal populist – also attended political rallies and shook hands with supporters in April, openly flouting social distancing rules. His rebound from the virus furthered the impression of an exceptional figure – an impression that maintained approval ratings.

In June, the Brazilian Government stopped publishing data around deaths and infections stemming from COVID-19, heightening accusations that it was attempting to hide the stark nature of deaths from Coronavirus in the country. Modi too has expressed a desire to control information and was reported to have personally asked the media to focus on “more positive” stories, while Johnson too frequently enjoys the company of a compliant media.

Exceptional responses

Last year, the UK’s Prime Minister proudly declared that he “shook hands with everybody” when visiting a hospital with COVID-19 patients.

Initially denying the scale of the virus, Johnson missed five COBRA meetings, while his official spokesperson did not deny the claim initially reported by the BBC that Johnson wanted to “ignore” the virus.

On Saturday, the Chief Minister of Maharashtra, Uddhav Thackeray, said he tried calling Modi to discuss shortages of oxygen and the drug remdesivir – but was informed that Modi was occupied addressing rallies.

As the UK became the epicenter of Europe’s COVID-19 outbreak in January, Johnson maintained that the Government had “done everything it could” to stop the spread of the virus, despite the Government being initially enamored by the concept of a ‘herd immunity’ approach to the virus.

Minutes after addressing a meeting of Conservative law-makers he described as packed in “cheek by jowl”, the Government warned the public against breaking social distancing rules. With a comparatively small population of 68 million, the UK has the seventh-largest number of infections globally, and 127,345 deaths – the fifth-largest in the world.

Ultimately, COVID-19 has exposed the myth of exceptionalism and comfortable complacency at the heart of the governments of India, Brazil and the UK.

Leaders such as Modi, Bolsonaro and Johnson construct the illusion of invincibility, but are not immune to a virus. State failure is responsible for hundreds of thousands of deaths and these populist leaders have come to embody it.

All three deserted their country in a time of collective grief, sorrow and frustration – maintaining not only good approval ratings, but the inexplicable impression that they truly did everything they could. It would be instructive to ask ourselves: why?

*The writer is a freelance writer who frequently writes on education, politics and mental health.

April 25. 2021

The viewpoints expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the opinions, viewpoints and editorial policies of Aequitas Review.