Indian Americans love Kamala Harris. The daughter of an Indian biologist who moved to the United States and became one of the country’s most respected cancer researchers, Harris embodies the values of hard work, intellectual accomplishment, and political engagement. As a US senator, she pushed for immigration policies favored by the Indian American community, including a lifting of country caps on H1-B temporary employment visas and the retention of employment rights for spouses of H1-B visa holders. And Indian Americans are understandably proud to see one of their own rising to the top of the US political system.

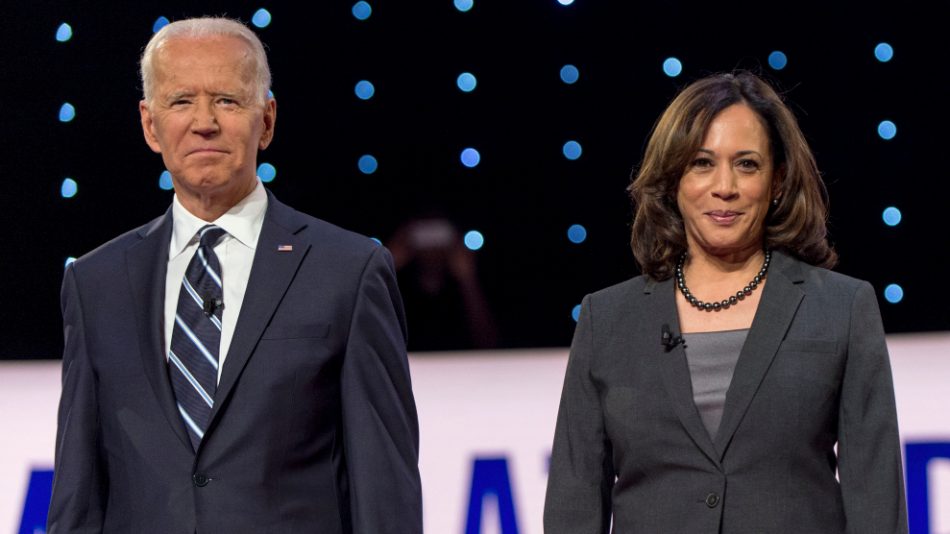

But good for Indian Americans does not necessarily mean good for the current government of India. On the contrary: The Biden team’s priorities (from what we know so far) are likely to drive a wedge between the United States and continental Asia’s oldest democracy at a time when Washington is looking for new allies in its strategic rivalry with China.

Harris may be a part of that wedge herself. As senator, Harris has been diplomatically circumspect in her few public comments about India’s government but has shown no love for Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Last year, she even publicly criticized Indian Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar while he was on an official visit to the United States. Jaishankar had refused to share a platform with US Rep. Pramila Jayapal, the Indian American sponsor of a House of Representatives resolution calling out the Indian government for its policies in Kashmir.

Harris’s own family connection to India may color her attitude. Her mother hailed from Tamil Nadu in southern India, a state in which Modi’s BJP did not win a single seat in last year’s national parliamentary elections. The BJP is often described as a Hindu nationalist party, but it can also be seen as a regional movement centered on the Hindi heartland of northern India. That regional base has expanded in recent years, but Tamil Nadu—which is almost 90 percent Hindu but not Hindi-speaking—remains a bastion of opposition.

Harris herself has been critical of the Indian government’s policies in Kashmir and strongly suggested (without explicitly saying) that she would put human rights at the center of her approach to India—and the rest of the world. That sounds like political boilerplate until you realize that in India, “human rights” often translates as “anti-BJP.” Unable to beat Modi at the polls, his domestic critics have focused on what they say are policies and incitement directed against minorities, such as India’s 172 million Muslims. With Harris in the West Wing, Modi’s opponents in India may suddenly have much more leverage at their disposal.

*The writer is an adjunct scholar at the Centre for Independent Studies in Sydney and an associate professor at the University of Sydney.

(Foreign Policy)

November 8, 2020

The viewpoints expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the opinions, viewpoints and editorial policies of Aequitas Review.